Policy Background

Policymaking stemming from the 1980’s War on Drugs has dramatically increased the number of people arrested and incarcerated in Texas for drug offenses. In 2019, nearly 700,000 people were arrested in Texas — 128,000 for drug violations alone.1 Low-income people with substance use disorders must wait weeks for intensive residential, outpatient, and medication-assisted treatment.2 People in need of co-occurring psychiatric and substance abuse treatment also must wait weeks for specialized services.3

Texas’ inadequate treatment infrastructure means people with drug use problems are far more likely to be arrested than to receive help. Over the past five years, nearly all serious and violent offense cases have declined significantly in Texas, whereas drug possession cases have increased nearly 25 percent.4 The cycle of substance use, arrest, and incarceration simply continues — ravaging families, perpetuating Texas’ drug crisis, and squandering resources that could be used to truly prevent crime.

“This growth [in incarceration] has occurred at great public expense, despite the fact that research shows public health responses to drug use are more effective than criminal justice responses and incarcerating people for drug offenses has a questionable impact on public safety. In fact, a recent analysis of state corrections and public health data found no relationship between imprisonment rates and rates of drug use, overdose deaths, or arrests for drug law violations. In other words, evidence shows more punitive criminal justice responses such as felony convictions are not effective tools to deter drug use or mitigate the harm it can cause.”10

Rather than restoring people to wellness, low-level drug enforcement worsens the conditions that perpetuate drug use, and it does so disproportionately according to race and socioeconomic status. Of the more than 2.3 million Americans in prison or jail in 2019, nearly 60 percent were Black or Latinx,5 who collectively comprise only 31.7 percent of the total U.S. population.6 In addition, it is impossible to ignore the socioeconomic disparities among those impacted by the drug war and incarceration. Nearly two-thirds of those incarcerated had incomes of less than $12,000 per year prior to entering prison.7

It is critical to decrease reliance on harmful policing strategies and criminalization of illicit drug use and instead prioritize harm reduction-based strategies. Punitive approaches have proven ineffective in reducing the availability of drugs, while actually causing harm, including increased incarceration and separation of families.8

Harm reduction comprises policies, programs, and practices that aim to minimize negative health, social, and legal impacts associated with drug use and drug policies. Its primary goal is to keep people alive and encourage positive change in their lives. Harm reduction is grounded in dignity, justice, and human rights — working with people without judgment, coercion, or discrimination and without requiring them to stop drug use as a condition of support. Numerous studies confirm that harm reduction prevents overdose, lowers incidence of diseases including HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis, and supports recovery for those who seek it.9

Substance use disorder is inherently a public health issue. It can be managed in the community with treatment and support — not through costly and unnecessary policing and incarceration. To reduce the number of people in Texas prisons and jails, it is critical to ensure that those struggling with substance use disorder have the tools to safely manage addiction issues and live productive lives in the community.

Proposed Solution

To more effectively and safely address substance use in communities, Texas leadership should:

1. Lower penalties for minor drug possession offenses from a felony to a misdemeanor, which will give more people the opportunity to take drug-related educational courses or engage in community service rather than be incarcerated.

Also importantly, decreasing penalties for possession will allow the state to shift a portion of the savings from lowered incarceration into local communities, which can invest in needed services such as certified peer support, recovery housing, or virtual outpatient or inpatient treatment.

2. Intentionally invest in harm reduction- and other community-based strategies that connect drug users with support services, reduce treatment waitlists, and, as necessary, improve probation outcomes — all of which act to reduce re-offending.

As of August 2020, approximately 2,200 people were serving time in state jail for possessing less than one gram of a controlled substance11 (the equivalent of a sugar packet); that number is likely to rise as court activity increases after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. The yearly taxpayer cost of incarcerating people for possessing small quantities of drugs is more than $42 million. This is a staggering sum considering that residents of most low-income communities must wait weeks or months to access affordable substance use treatment or recovery services. Localities should be able to invest in strategies that best serve their communities and help people get back on their feet, not be forced to treat drug use as a felony warranting state-level incarceration.

Relevant Bills

- Bill Number: HB 1086 [Moody]

Bill Caption: Relating to the criminal penalties for certain criminal offenses.

TCJE Materials: Fact Sheet

- Bill Number: HB 169 [Senfronia Thompson, Reynolds]

Bill Caption: Relating to the criminal penalties for the possession of small amounts of Penalty Group 1 controlled substances and marihuana.

- Bill Number: HB 1954 [Dutton]

Bill Caption: Relating to the penalty for certain offenders for possession of a small amount of certain controlled substances.

- Bill Number: HB 266 [Senfronia Thompson]

Bill Caption: Relating to the criminal penalty for possession of certain small amounts of controlled substances in Penalty Group 1.

- Bill Number: SB 1005 [Hinojosa]

Bill Caption: Relating to the punishment for certain controlled substance possession offenses under the Texas Controlled Substances Act; changing eligibility for community supervision.

- Bill Number: HB 894 [Wu]

Bill Caption: Relating to placement on community supervision of a defendant convicted of certain felony possession offenses under the Texas Controlled Substances Act; changing eligibility for and conditions of community supervision.

- Bill Number: HB 2190 [White]

Bill Caption: Relating to the prosecution of and punishment for certain state jail felony offenders, including the creation of a pretrial intervention program for certain state jail felony offenders; authorizing a fee.

- Bill Number: HB 2442 [White, Allen]

Bill Caption: Relating to the creation of the Justice Reinvestment Incentive Program.

- Bill Number: HB 898 [White, Guillen]

Bill Caption: Relating to an interagency grant program to support and sustain the operations of community recovery organizations.

In light of Texas’ projected budget crisis, TCJE developed 7 cost-saving solutions. Learn more about our ”Spend Your Values, Cut Your Losses" campaign here, and read the full portfolio of solutions here.

1 “Crime in Texas 2019 — Texas Arrests, Summary of Arrest,” Texas Department of Public Safety, 19.

2 Data request, Texas Health and Human Services Commission, September 2017.

3 Mary Ann Priester et al., “Treatment Access Barriers and Disparities Among Individuals with Co-Occurring Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders: An Integrative Literature Review,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 61, 55 (2016).

4 Court Activity Database, District Criminal Court Dispositions, 2013–2017, Office of Court Administration.

5 “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie, 2019,” Prison Policy Institute.

6 “Quick Facts: United States,” U.S. Census Bureau.

7 “The Relationship Between Poverty & Mass Incarceration: How Does Mass Incarceration Contribute to Poverty in the United States,” Center for Community Change.

8 “Every 25 Seconds: The Human Toll of Criminalizing Drug Use in the United States,” ACLU and Human Rights Watch, October 2016.

9 Harm Reduction International.

10 “Reclassified: State Drug Law Reforms to Reduce Felony Convictions and Increase Second Chances,” The Urban Institute.

11 High Value Data Set, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ).

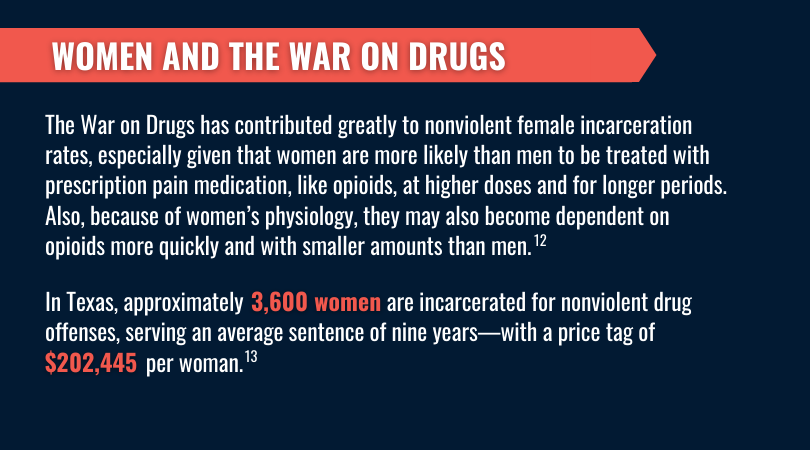

12 “Final Report: Opioid Use, Misuse, and Overdose in Women,” USDHHS, Office on Women’s Health, 2017.

13 “Criminal and Juvenile Justice Uniform Cost Report,” Legislative Budget Board, January 2017.