Report Data

Texas' state jail system went into effect in 1994. Its original architects never intend for people to be sentenced to incarceration without rehabilitative programming or community supervision. But today, courts routinely sentence defendants to terms of incarceration with little to no rehabilitation, reentry programming, or post-release supervision. In fact, of the 19,985 state jail discharges in 2016, only 87 people (0.4 percent) were released to community supervision.

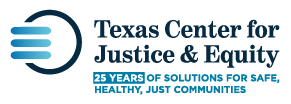

The results have become inevitable: People released from state jails have the highest rate of re-offending of any population released from a state correctional institution in Texas. The most recent state jail re-arrest rate as reported by the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) is nearly 63 percent, compared to 46 percent for prison releases.

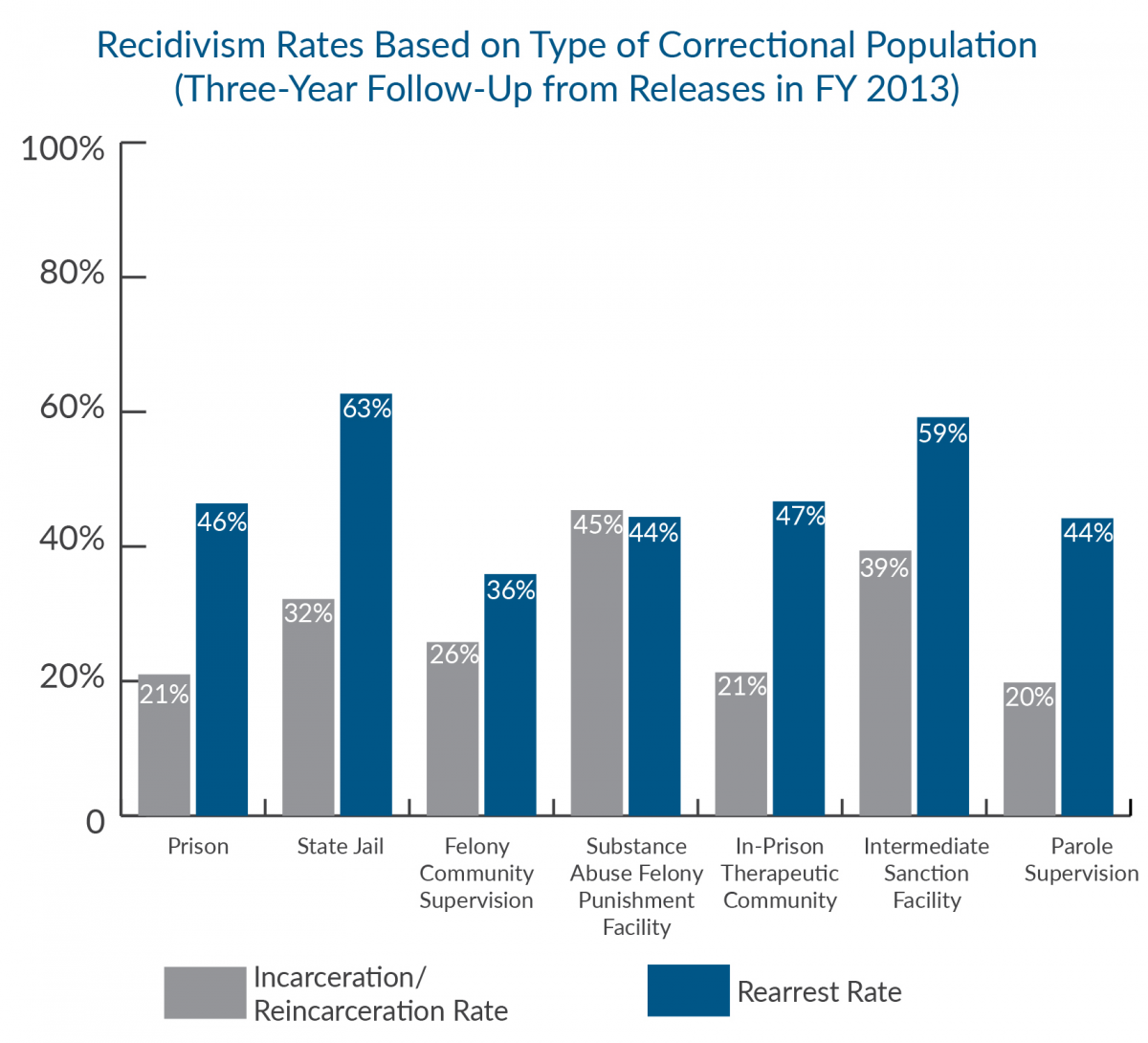

The Texas Center for Justice and Equity conducted a State Jail-Probation Study, which included 140 interviews, 89 with males incarcerated at Travis County State Jail, and 51 with females in Woodman State Jail. We found that when asked about probation, a surprisingly small percentage of interviewees — 11 percent of males and 18 percent of females — had been offered probation but refused and instead opted for state jail incarceration. Probation was not offered to 66 percent of male interviewees and 27 percent of female interviewees. Many interviewees — 55 percent of women and 22 percent of men — had been placed on probation but were not able to meet the conditions; they were revoked and are now in state jail.

Costs were cited as a major barrier to the successful completion of community supervision. In our interviews, 43 percent of males and 71 percent of females said that probation simply costs too much. In addition to a monthly $60 supervision fee, probationers must pay court costs, as well as for classes, treatment expenses, drug screens, and more. The burden can be overwhelming — especially for women, single parents, young adults, and those struggling to find a job — leading to revocation to state jail.

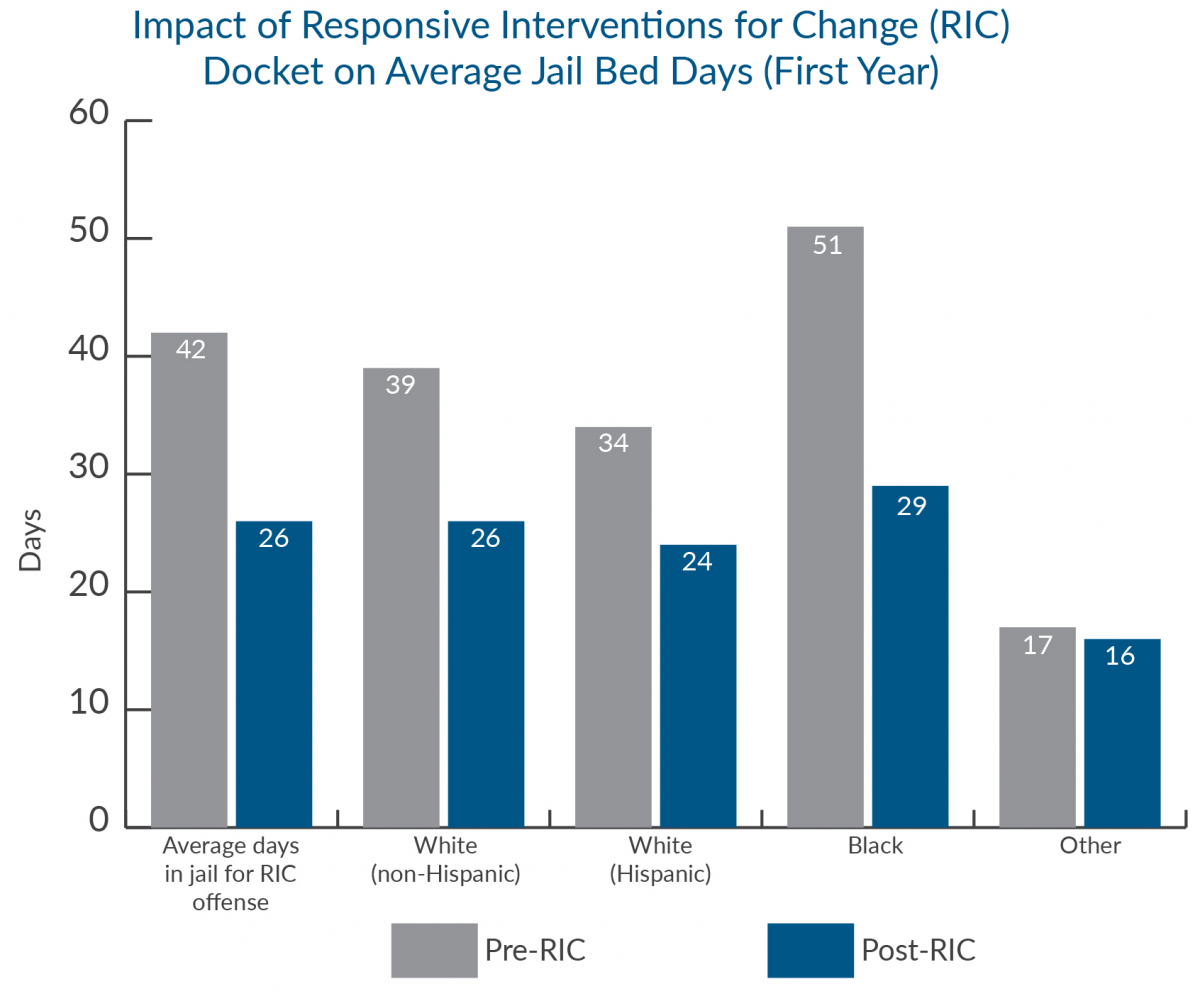

Data from Harris County indicates that its Responsive Interventions for Change court docket is diverting people from its county jail, state jail, and prison. In its first year of implementation, Harris County sent 424 fewer people to prison for drug possession, 600 fewer people to state jail, and 485 fewer people to county jail. The County also dismissed 1,412 more drug possession cases in 2017 than in 2016, an astonishing figure that is likely due to the emphasis on pretrial diversion for first-time offenses.

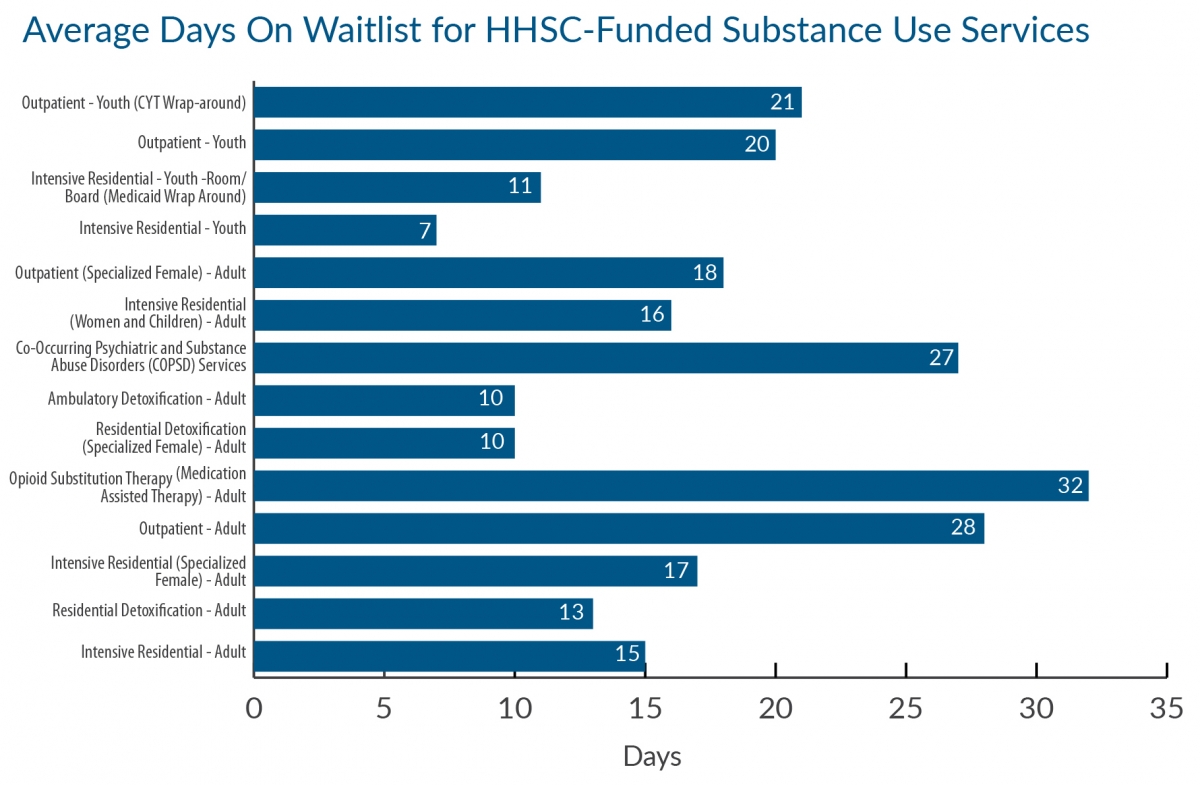

While the innovation in Harris County is remarkable, it does not entirely address a core problem with underlying behaviors — like possession of a controlled substance — that we classify as a criminal offense: A significant proportion of arrestees are dealing with inherent public health issues, not criminal justice issues. According to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC), low-income people with substance use disorder must wait more than two weeks for intensive residential treatment, four weeks for outpatient treatment, and almost five weeks for Medication-Assisted Treatment. People in need of co-occurring psychiatric and substance abuse treatment, who are already underserved, must wait almost four weeks for specialized services.

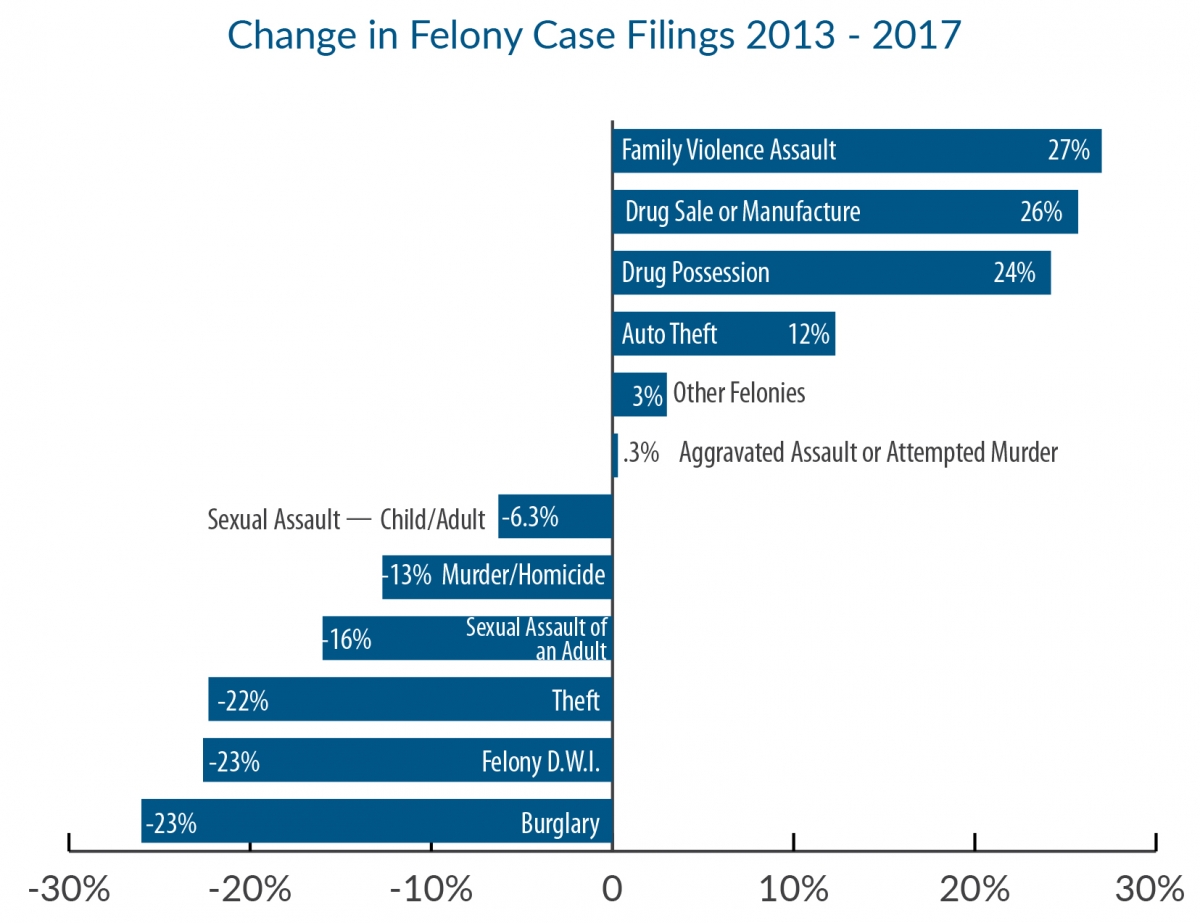

As a result, people with drug use problems are far more likely to be arrested than receive treatment in Texas. Over the past five years, nearly every category of serious and violent offense has declined significantly in this state, whereas drug possession cases have increased nearly 25 percent.

It can be accurately stated that the failures of the state jail felony system have contributed to substance use disorder becoming a public health crisis. With such high re-arrest rates among individuals with state jail offenses — a large percentage of whom were initially incarcerated on a drug-related charge — the cycle of substance use, arrest, and incarceration simply continues, at a massive cost to taxpayers and communities. This underscores the need to address public health issues outside the criminal justice system.