The data contained in our five-part report series unveils how Texas sends thousands of people into the criminal justice system at an astronomical expense to taxpayers each year. Through the series, we are better able to examine the policies that fail marginalized populations and suggest feasible solutions to divert these groups away from the Texas criminal justice system and into more effective community supports.

Below are findings from the first three reports. They demonstrate how the criminal justice system wastes taxpayer dollars that could be better invested in community solutions that serve the needs of young adults on probation, as well as people at risk of a state jail felony conviction.

Young Adults and Community Supervision: The Need for a Developmentally Appropriate Approach to Probation

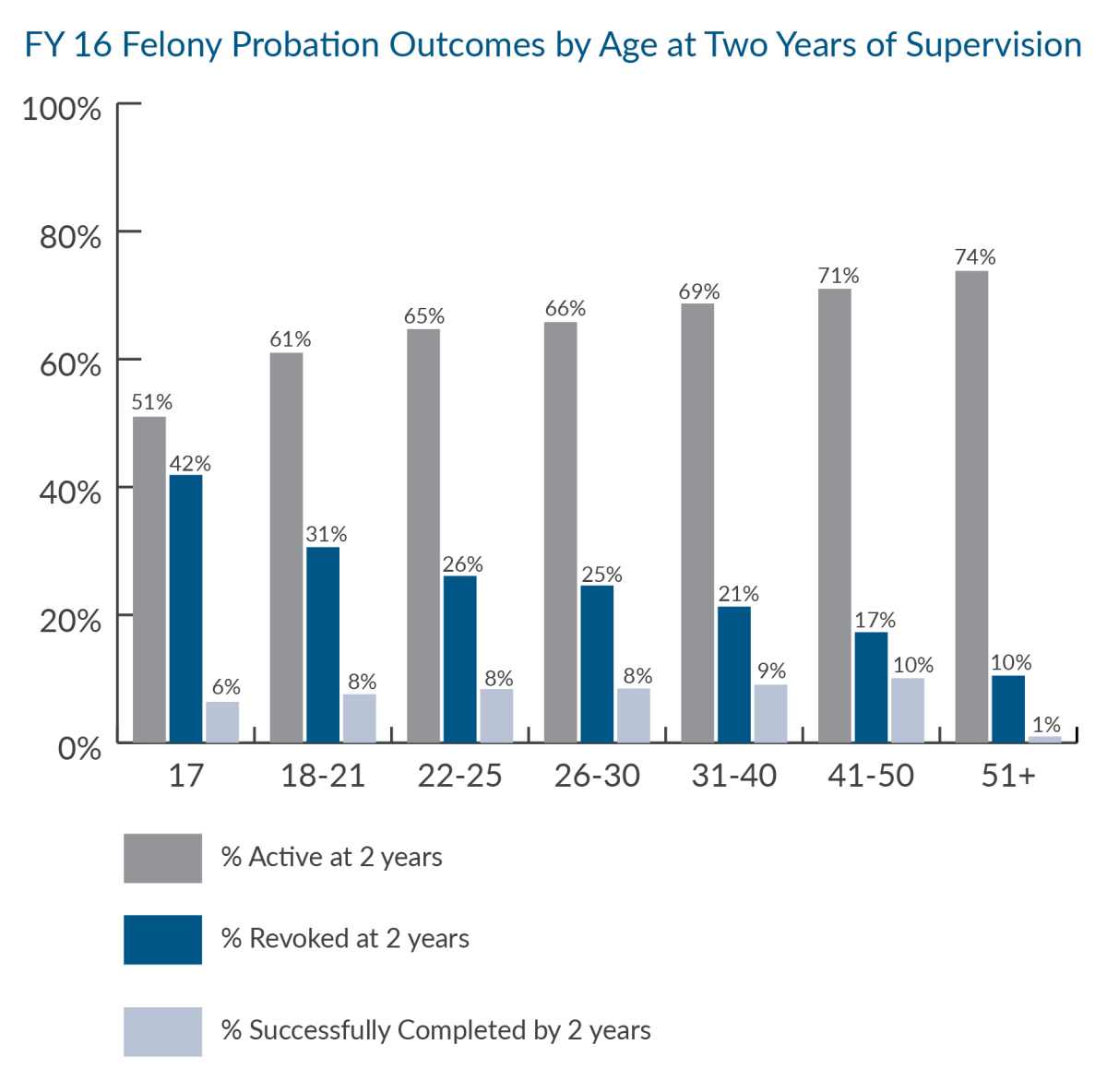

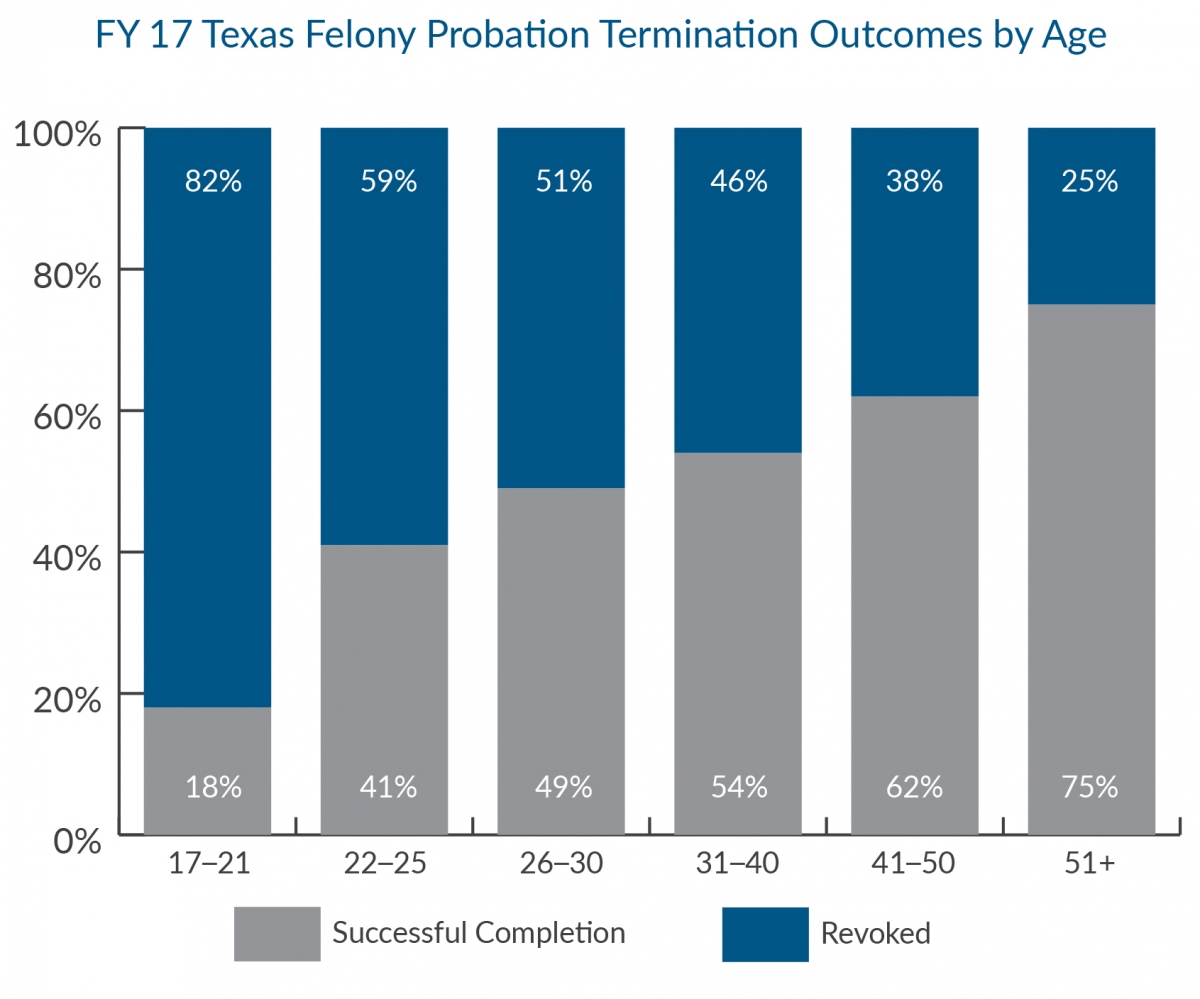

Young adults are less likely than older adults to have remained on probation for the full term by the two-year point, and the majority of cases terminated by the two-year point were due to revocation rather than successful completion.

In fact, only 18 percent of 17- to 21-year-olds successfully completed and were terminated from felony probation in FY 2017. The rate was slightly better for 22-to 25-year-olds, with 41 percent successfully completing and being terminated from probation, compared to 60 percent of felony probationers over age 25. Sadly, nearly 7,400 young men and women had their probation revoked in FY 2017, with 7,000 young people committed to prison or jail.

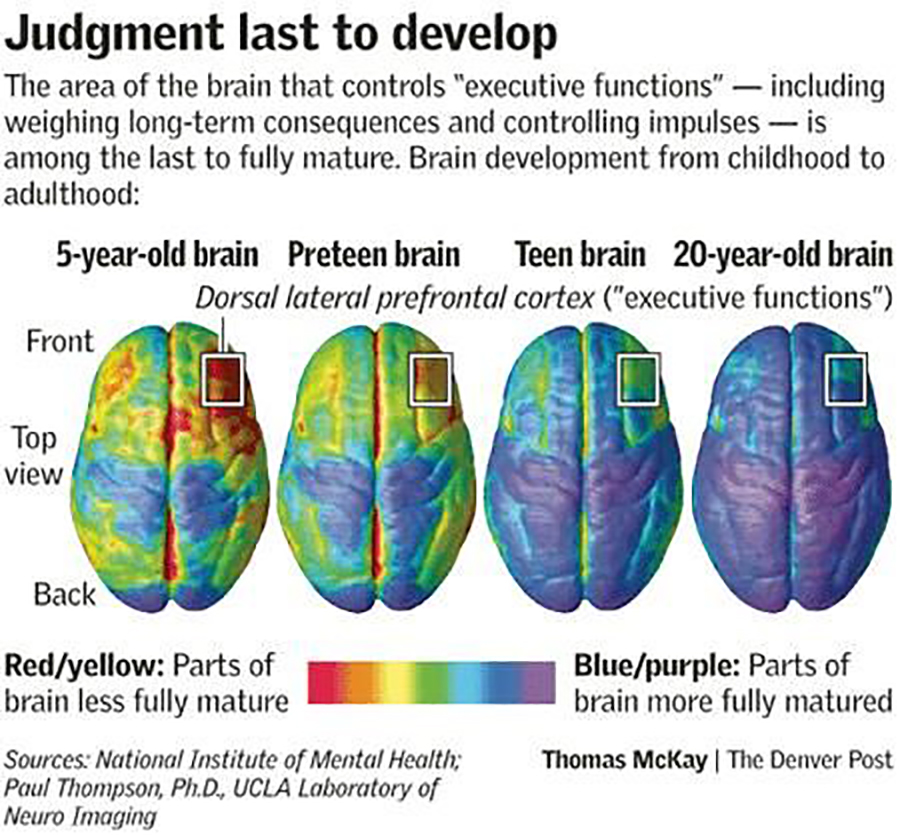

Recent neuroscience research helps explain why young adults require specialized, age-appropriate interventions. The brain — and, in particular, the prefrontal cortex — continues to develop well into an individual’s twenties.

Young adults with a history of foster care placement are at particular risk of criminal justice system involvement. Nearly 70 percent of young males involved in the foster care system are arrested after leaving foster care, a rate that is 23 times higher than the general population; and 55.2 percent are convicted of a crime after leaving foster care.

The current standards of community supervision are ineffective for young adults and costly to taxpayers. In 2017, the 7,000 young people on adult felony probation who were incarcerated after a probation violation cost the state over $130 million. In comparison, if these young adults remained on standard probation, it would cost taxpayers approximately $4.5 million — a savings of $126 million.

A Failure in the Fourth Degree: Reforming the State Jail Felony System in Texas

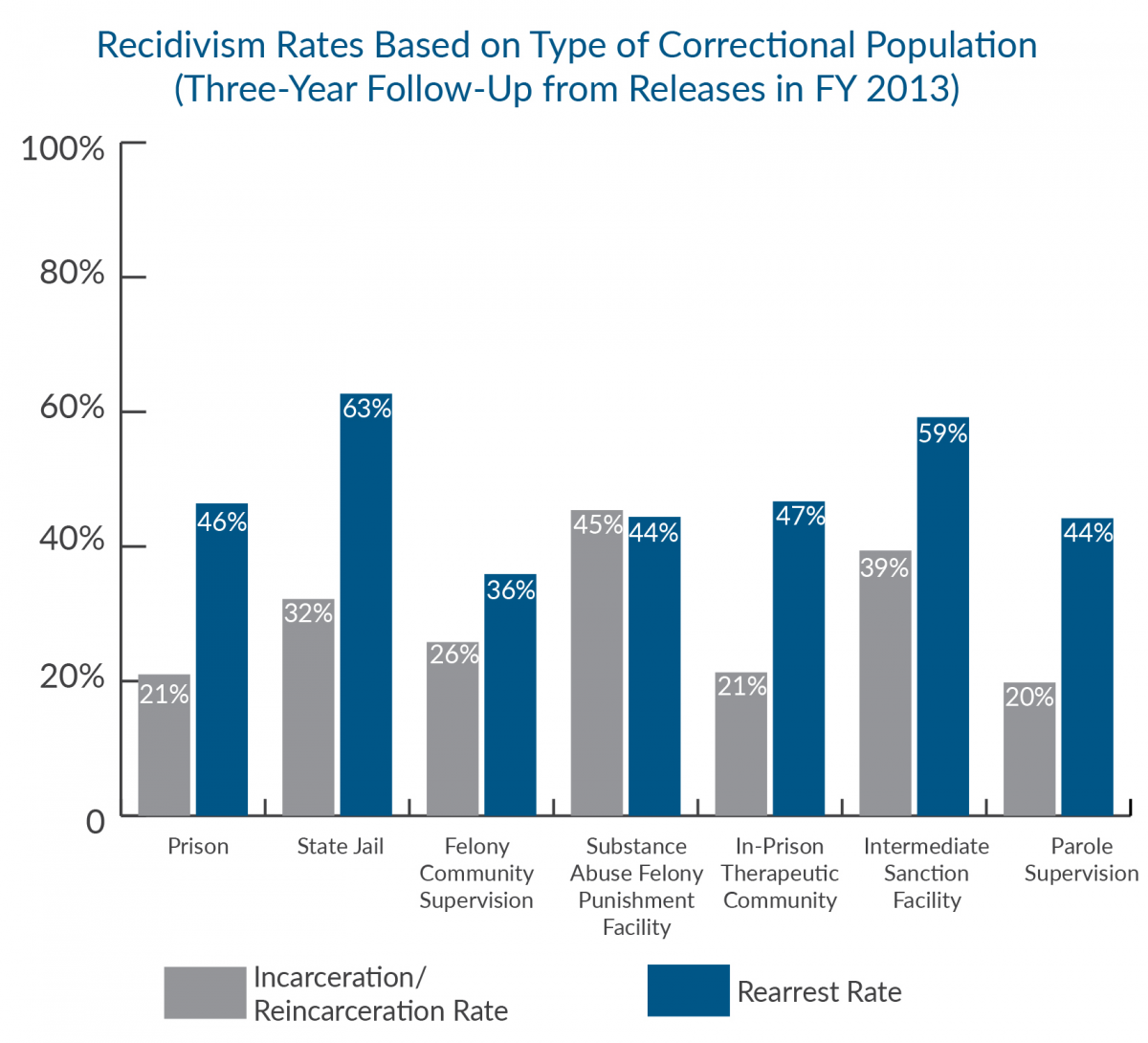

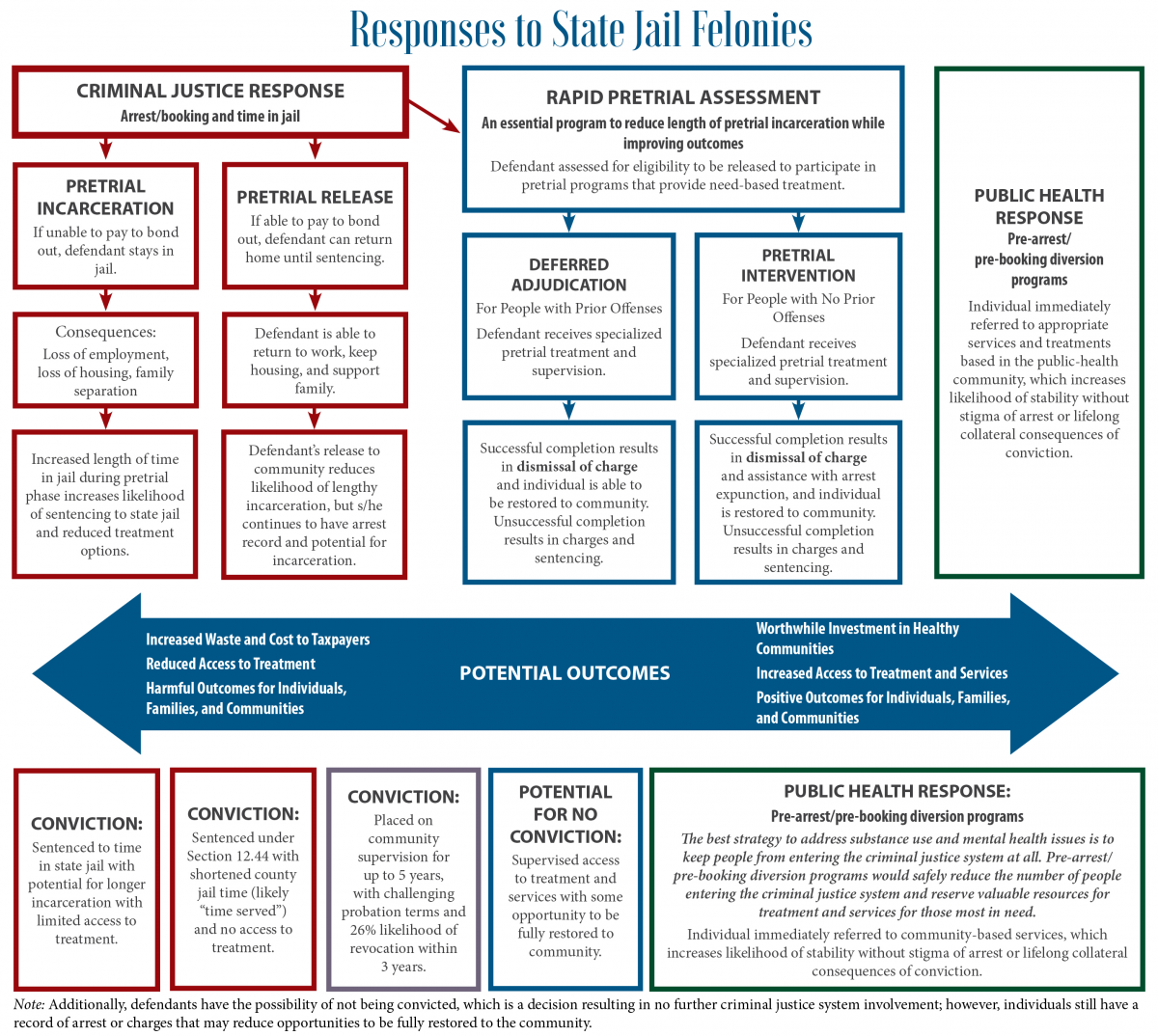

Texas' state jail system went into effect in 1994. Its original architects never intend for people to be sentenced to incarceration without rehabilitative programming or community supervision. But today, courts routinely sentence defendants to terms of incarceration with little to no rehabilitation, reentry programming, or post-release supervision. In fact, of the 19,985 state jail discharges in 2016, only 87 people (0.4 percent) were released to community supervision.

The results have become inevitable: People released from state jails have the highest rate of re-offending of any population released from a state correctional institution in Texas. The most recent state jail re-arrest rate as reported by the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) is nearly 63 percent, compared to 46 percent for prison releases.

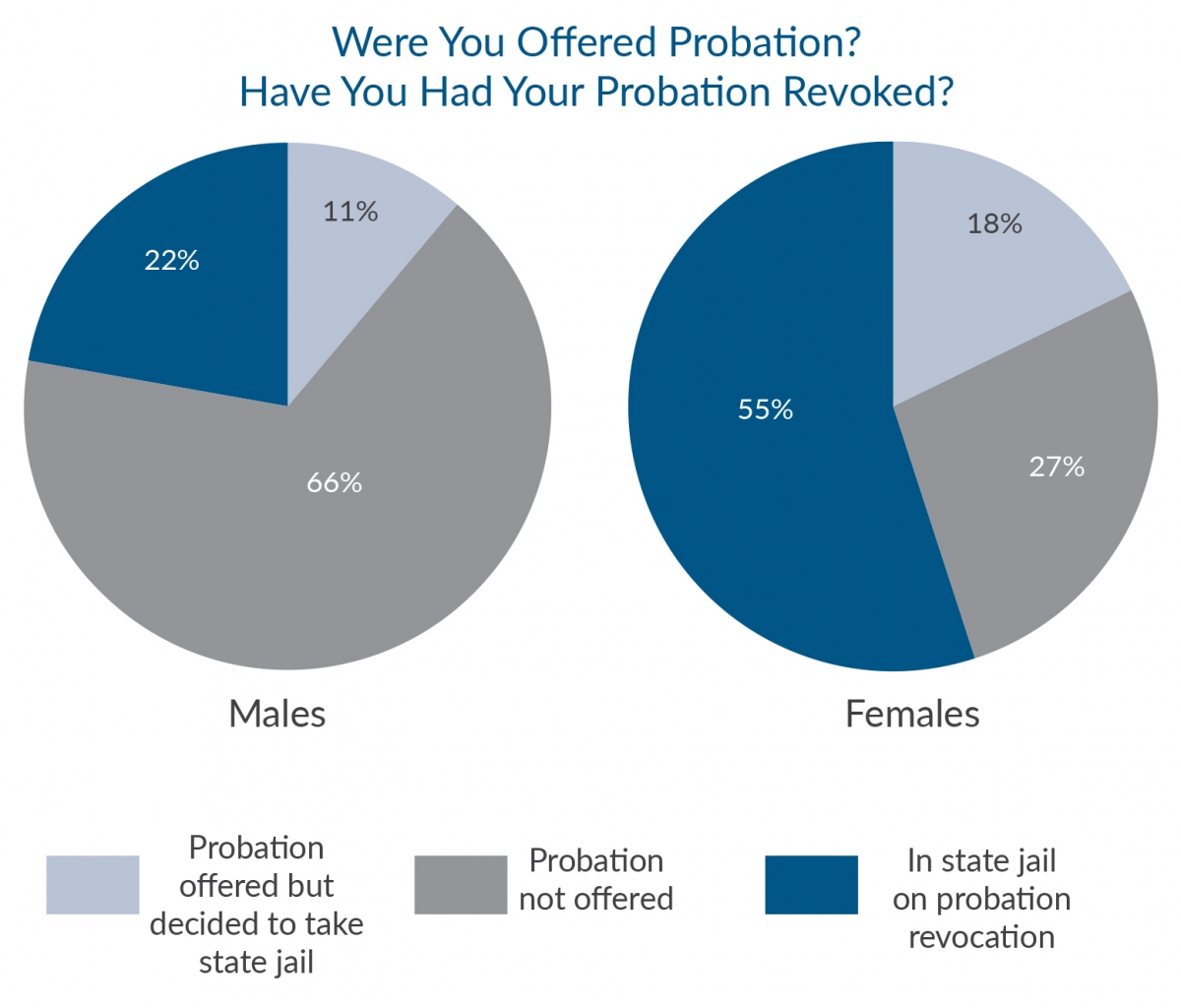

The Texas Center for Justice and Equity conducted a State Jail-Probation Study, which included 140 interviews, 89 with males incarcerated at Travis County State Jail, and 51 with females in Woodman State Jail. We found that when asked about probation, a surprisingly small percentage of interviewees — 11 percent of males and 18 percent of females — had been offered probation but refused and instead opted for state jail incarceration. Probation was not offered to 66 percent of male interviewees and 27 percent of female interviewees. Many interviewees — 55 percent of women and 22 percent of men — had been placed on probation but were not able to meet the conditions; they were revoked and are now in state jail.

Costs were cited as a major barrier to the successful completion of community supervision. In our interviews, 43 percent of males and 71 percent of females said that probation simply costs too much. In addition to a monthly $60 supervision fee, probationers must pay court costs, as well as for classes, treatment expenses, drug screens, and more. The burden can be overwhelming — especially for women, single parents, young adults, and those struggling to find a job — leading to revocation to state jail.

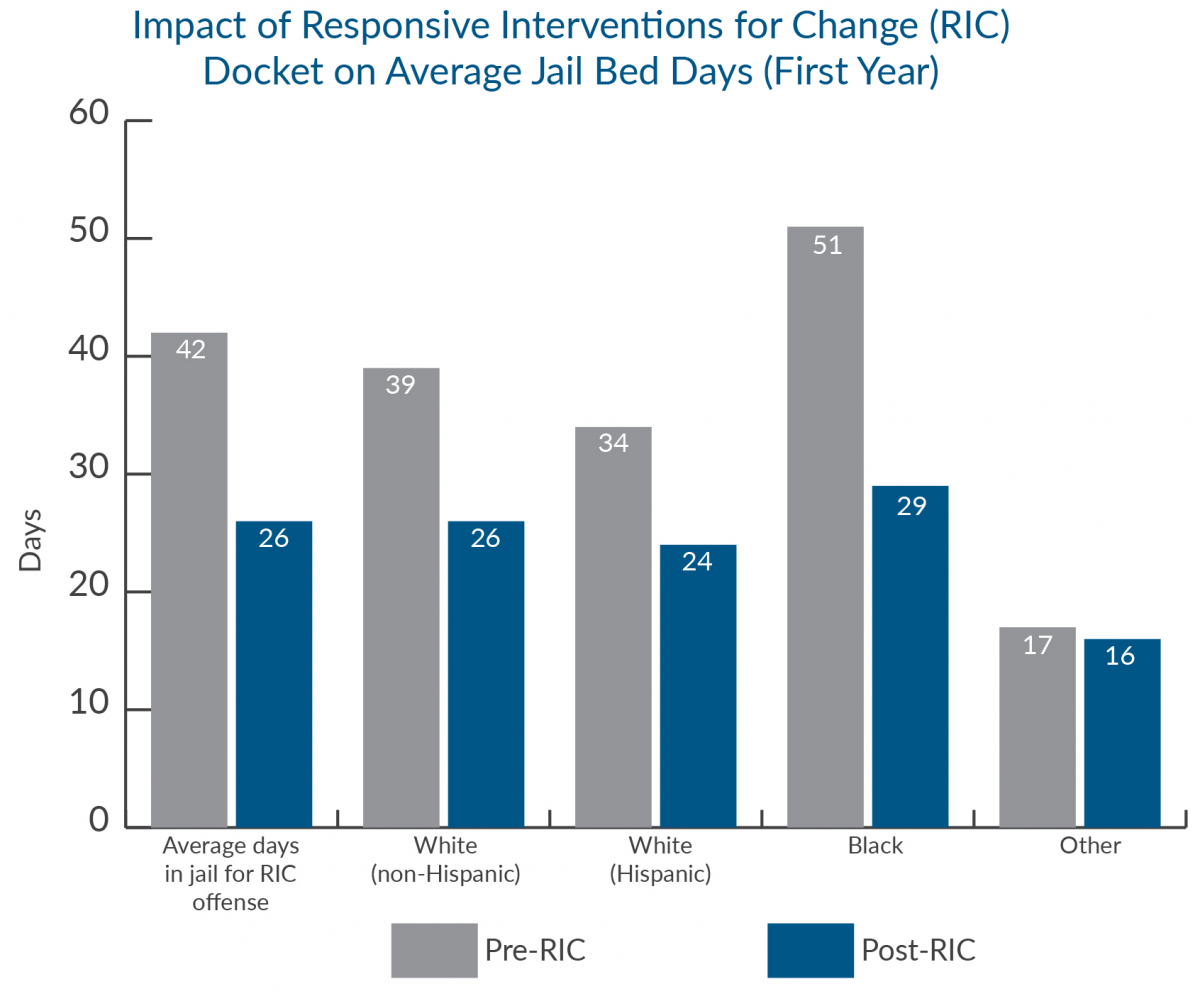

Data from Harris County indicates that its Responsive Interventions for Change court docket is diverting people from its county jail, state jail, and prison. In its first year of implementation, Harris County sent 424 fewer people to prison for drug possession, 600 fewer people to state jail, and 485 fewer people to county jail. The County also dismissed 1,412 more drug possession cases in 2017 than in 2016, an astonishing figure that is likely due to the emphasis on pretrial diversion for first-time offenses.

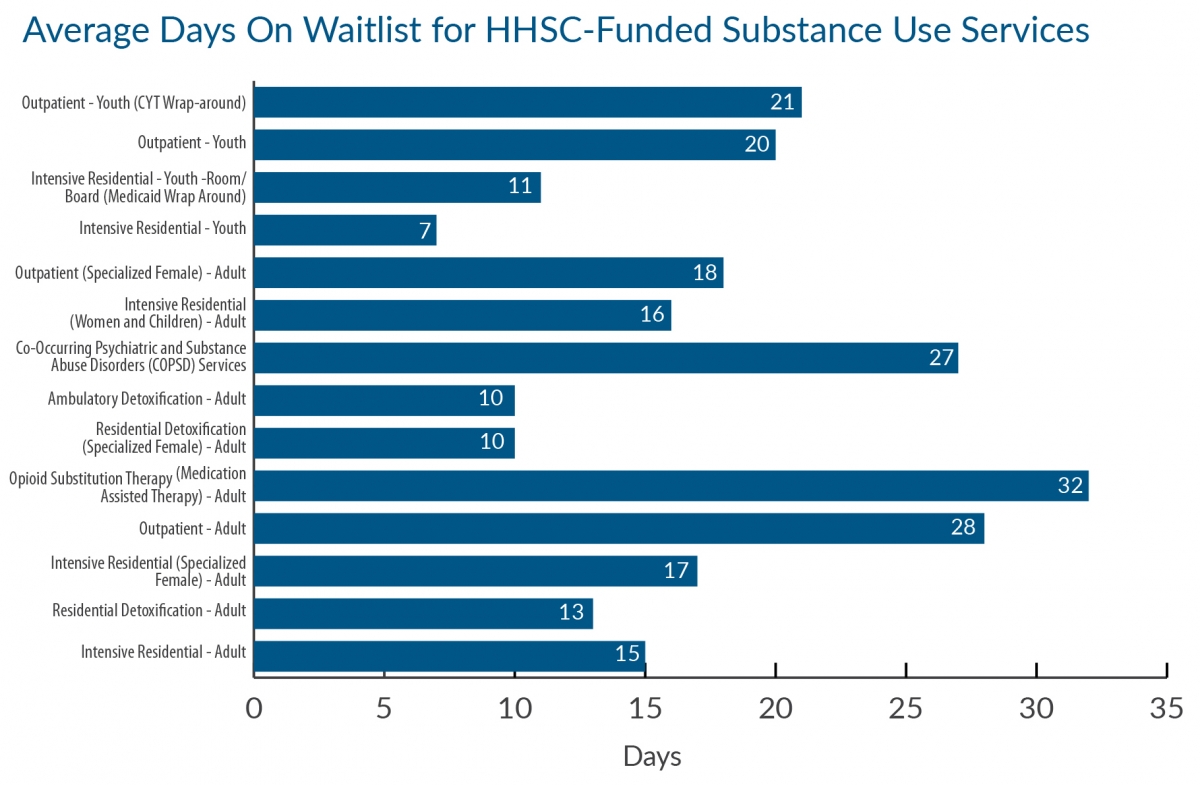

While the innovation in Harris County is remarkable, it does not entirely address a core problem with underlying behaviors — like possession of a controlled substance — that we classify as a criminal offense: A significant proportion of arrestees are dealing with inherent public health issues, not criminal justice issues. According to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC), low-income people with substance use disorder must wait more than two weeks for intensive residential treatment, four weeks for outpatient treatment, and almost five weeks for Medication-Assisted Treatment. People in need of co-occurring psychiatric and substance abuse treatment, who are already underserved, must wait almost four weeks for specialized services.

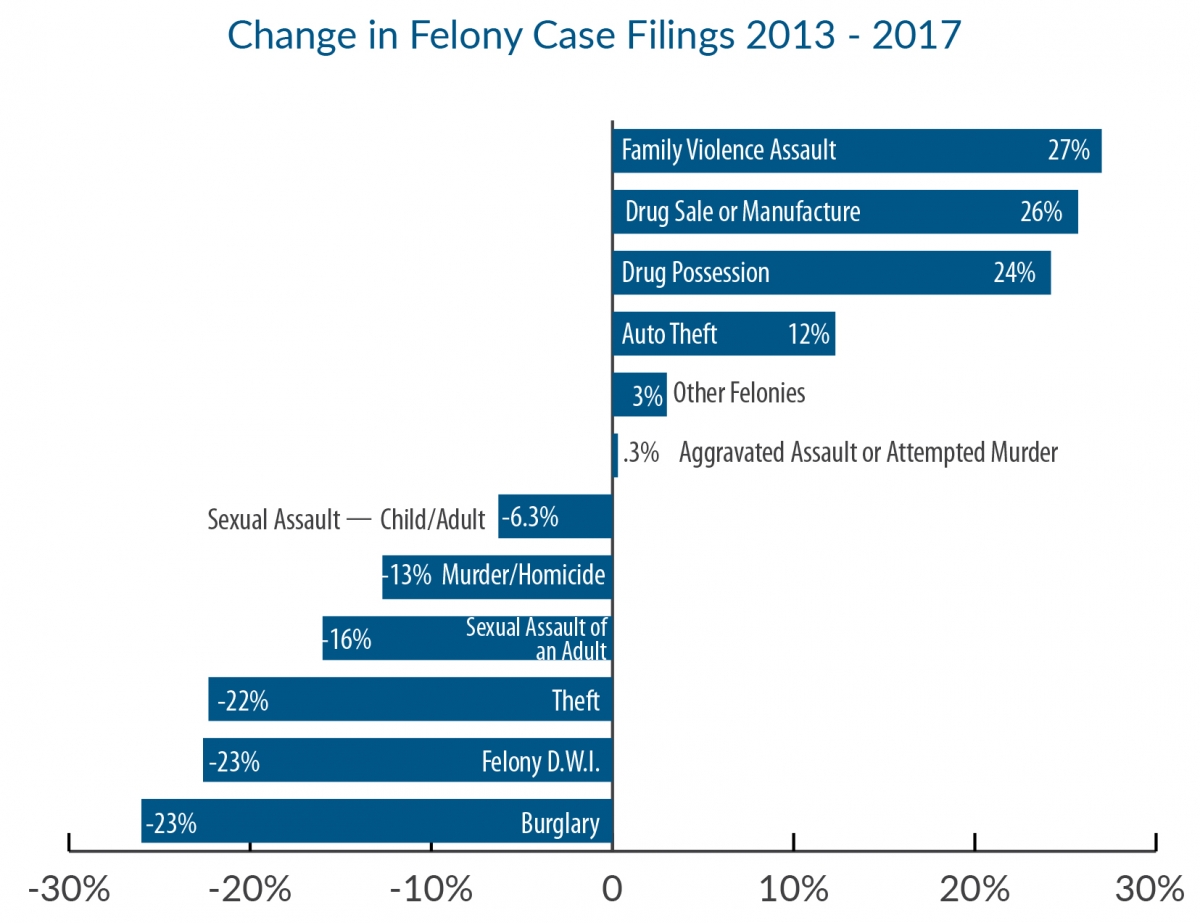

As a result, people with drug use problems are far more likely to be arrested than receive treatment in Texas. Over the past five years, nearly every category of serious and violent offense has declined significantly in this state, whereas drug possession cases have increased nearly 25 percent.

It can be accurately stated that the failures of the state jail felony system have contributed to substance use disorder becoming a public health crisis. With such high re-arrest rates among individuals with state jail offenses — a large percentage of whom were initially incarcerated on a drug-related charge — the cycle of substance use, arrest, and incarceration simply continues, at a massive cost to taxpayers and communities. This underscores the need to address public health issues outside the criminal justice system.

Out of Sight: LGBTQ Youth and Adults in Texas’ Justice Systems

LGBTQ Youth and Texas’ Justice Systems

LGBTQ youth, especially those who are transgender or GNC, Black, or Latinx, are more likely than non-LGBTQ youth to come into contact with law enforcement. Nationally, 13%–15% of youth who come into contact with the criminal justice system are LGBTQ, and roughly 300,000 LGBTQ youth are arrested and/or detained each year. LGBTQ youth of color are vastly overrepresented in the juvenile justice system where more than 60% are Black or Latinx.

The following sections explore the myriad factors that push LGBTQ youth toward the justice system and cause discrepancies in rates of incarceration for LGBTQ youth.

Family Rejection and Estrangement: On average, one-third of parents reject their children after they come out as LGBTQ. When LGBTQ youth experience family rejection after coming out, they are eight times more likely to attempt suicide. Lack of family backing in getting LGBTQ children access to mental health care and other support increases the likelihood that youth will come into contact with the justice system during a mental health crisis.

Homeless, Unsheltered, and Displaced LGBTQ Youth: Homelessness also exposes LGBTQ youth to interactions with law enforcement. Law enforcement officers also typically stop and arrest unsheltered LGBTQ youth on charges connected to survival rather than malicious intent. In 2016, the majority of the 49,957 arrests of juveniles in Texas were for charges that can be associated with homelessness and survival.

Foster Care System Involvement: One national survey showed 54% of homeless LGBTQ youth respondents had been sexually, physically, or emotionally abused by family members before they became homeless. LGBTQ youth are twice as likely as non-LGBTQ youth to live in a foster or group home. Nearly 23% of LGBQ youth in the juvenile justice system have experience in the foster care system compared to only 3% of non-LGBQ youth.

Mental Health Conditions and Substance Use: Family strife during the coming out and self-identification process can result in a significant amount of stress and trauma for LGBTQ youth. One study found 18% of LGB youth had experienced major depression in the past year, 11% met the criteria for PTSD, and 31% reported suicidal behavior at some point in their lifetime. Suicidal behavior among youth directly pushes them toward the justice system.

Unsafe Schools and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A 2015 study conducted in Texas found that 78% of students surveyed experienced verbal harassment from peers due to their sexual orientation; 58% were verbally harassed due to their gender expression; 35% reported physical harassment by other students because of their sexual orientation; and 26% reported physical harassment due to their gender expression. Additionally, forms of discipline and forcible removal from school increase the risk that LGBTQ students, especially students of color, will come into contact with the justice system.

LGBTQ Adults and Texas’ Justice Systems

Although they make up 3%–5% of the general adult population in the U.S., LGBTQ adults are vastly overrepresented in jails and prisons across the country. The National Inmate Survey (NIS) conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics shows 6% of men in jails and 9% of men in prisons identify as gay, bisexual, or as having had sex with other men. Nationwide, over 36% of women in jails and 42% of women in prisons identify as lesbian, bisexual, or as having had sex with other women.

There are a number of factors that increase the liklihood that LGBTQ adults become involved in the criminal justice system:

Mental Health Conditions and Substance Use: LGBTQ adults experience higher rates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality than non-LGBTQ adults. LGBTQ people are three times more likely than the general population to live with major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, thoughts of suicide, or substance abuse disorder.

Employment, Housing, and Identification Discrimination: Lawful discrimination is a precursor to justice system involvement and increases the likelihood that LGBTQ people in Texas will become unsheltered or homeless, be unable to access appropriate medical care, be unable to maintain a job, or live in poverty. Without stable housing, income, and access to health care, many LGBTQ people must rely on survival economies to meet their needs, which increases the possibility of sexual exploitation and incarceration. Of the 2,628 felony prostitution arrests of individuals in Texas with three or more prior arrests between May 2017 and April 2018, only 146 were provided services and programming through community supervision.

Incarcerated LGBTQ people are alao more likely to experience abuse and harassment by staff and others in the correctional facility, improper placement and solitary confinement, and denial of health care and programming. Many LGBTQ people do not identify as LGBTQ at intake to avoid abuse, violence, and mistreatment.

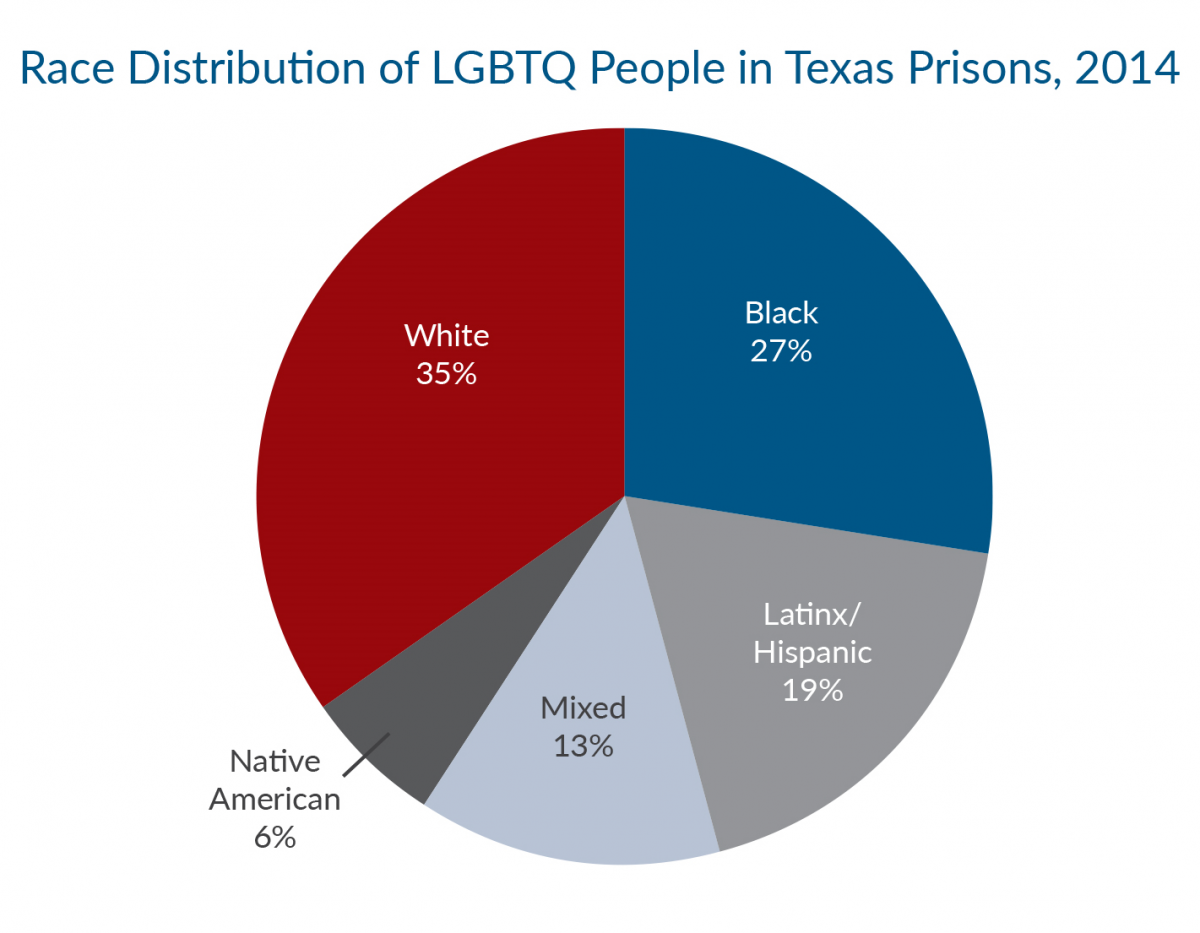

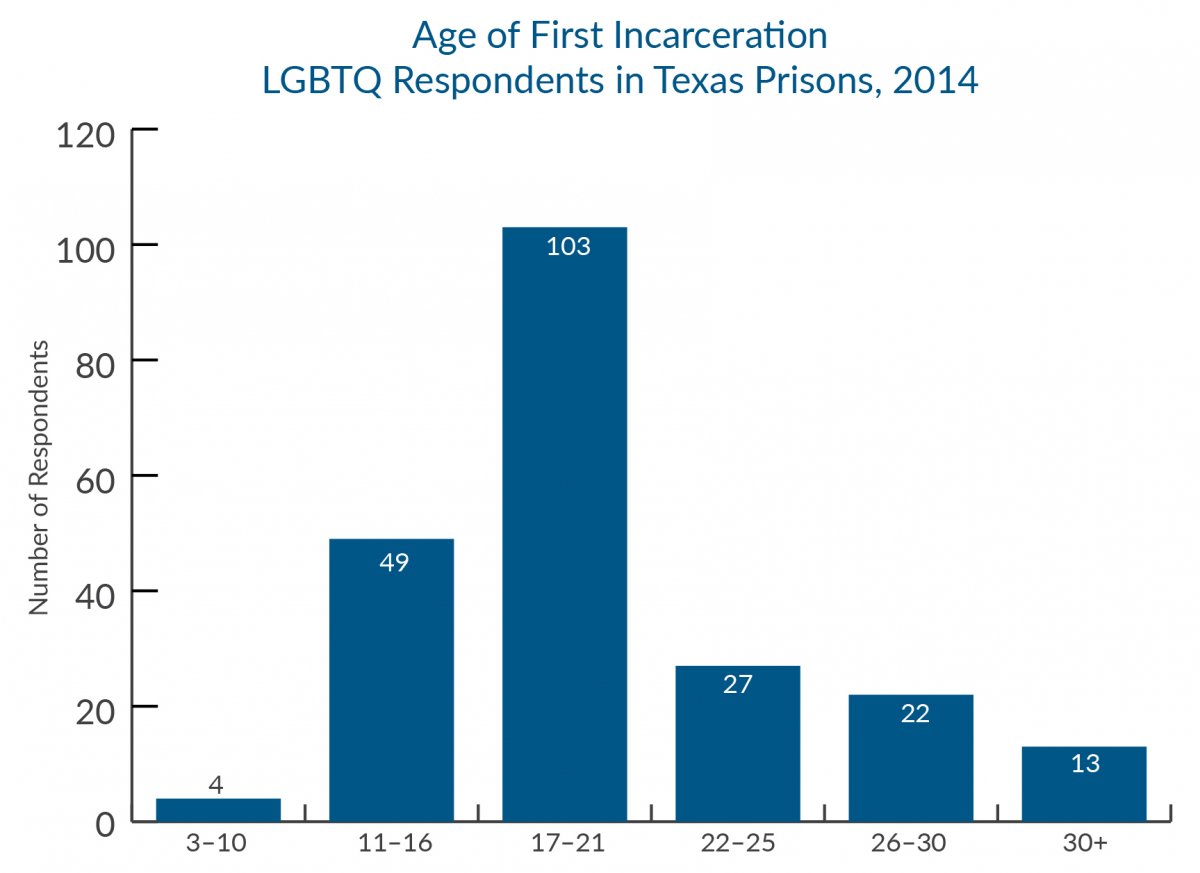

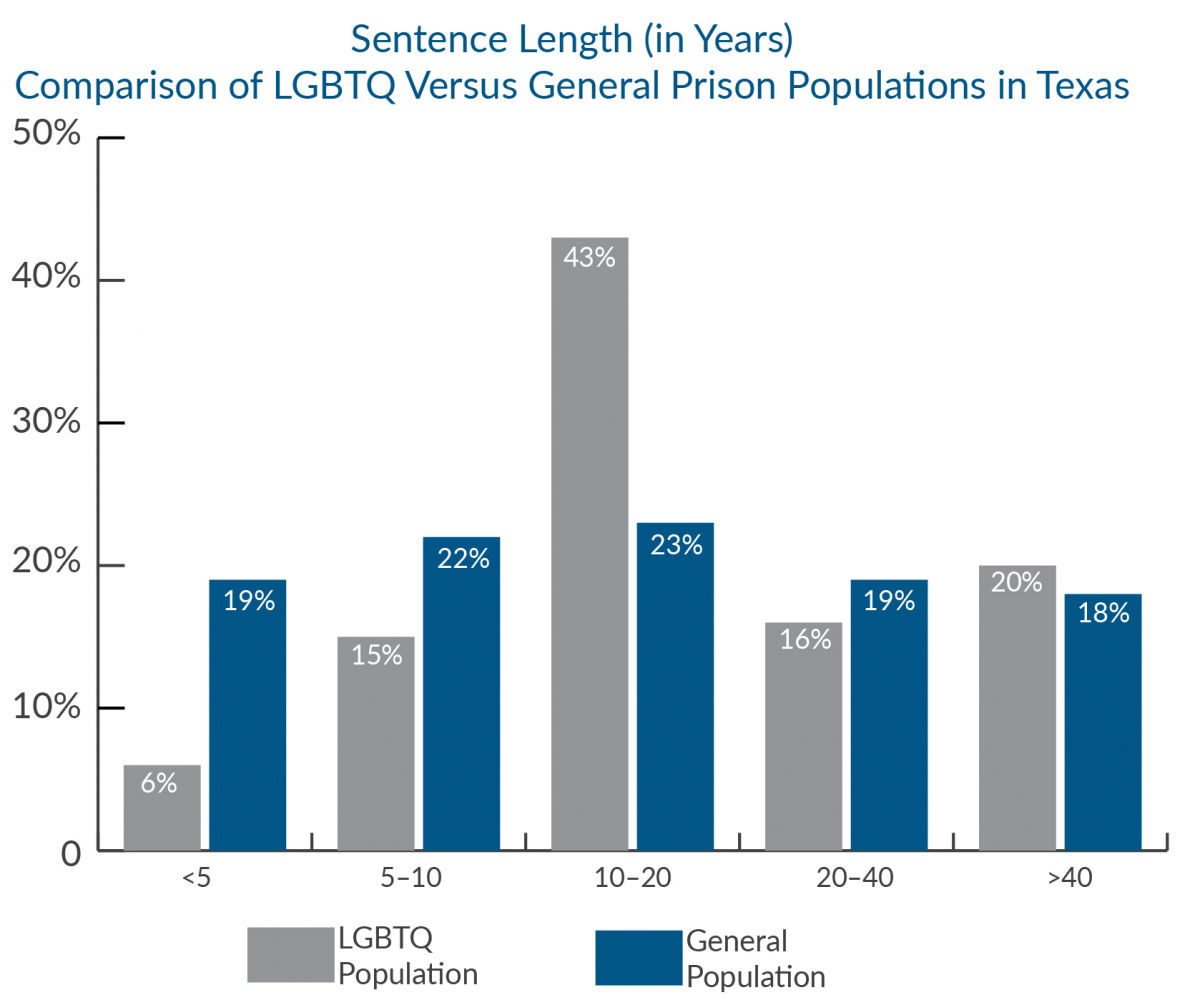

Findings from the Black and Pink Survey

Of the 245 respondents in Texas prisons, 59% identified as LGBTQ before incarceration, 65% struggled with substance abuse, and 58% were diagnosed with a mental illness. Additionally, Black LGBTQ adults are overrepresented among prison populations, LGBTQ adults tend to receive longer sentences and thus stay in prison until older ages, most were first incarcerated before the age of 22, and the majority of LGBTQ adults in prison have been incarcerated more than once.