Report Data

Intersection and Demographics

Intersection and Demographics

People experiencing homelessness are 11 times more likely to face incarceration when compared to the general population, and formerly incarcerated individuals are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. In fact, the rate of homelessness among adult state and federal prison inmates is four to six times the annual rate of homelessness in the general population.

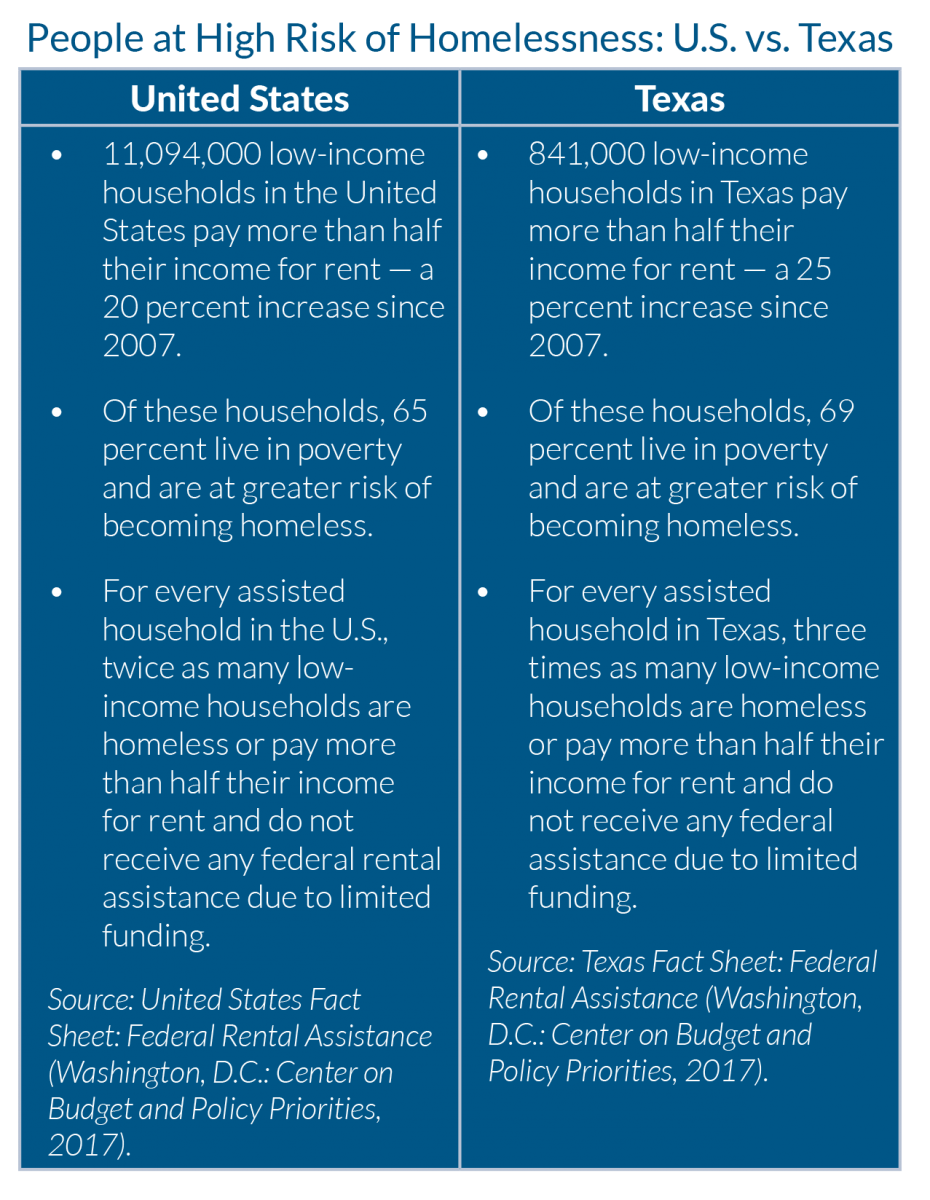

African Americans in Texas are disproportionately impacted by homelessness - a disturbing trend linked with the overincarceration of people of color in Texas. While Black individuals comprise only 12.7 percent of the Texas population, they represent 38.2 percent of the homeless population, indicating that Black individuals are overrepresented in the homeless population by three times their proportion of the Texas population. This rate of disproportionality exceeds even the overrepresentation of Black individuals in the Texas prison system. Black individuals comprise 33% of the Texas prison population, a rate of disproportionality 2.67 times their share of the Texas population.

Certain demographics that have been associated with both homelessness and the risk of criminal justice system involvement include being male, single, of poor economic standing, of an ethnic minority, and of low education. Additionally, certain characteristics such as mental illness, substance use, and lack of employment create unique challenges that make it difficult for this population to escape the pattern.

Mental Health Conditions

A national survey found that, prior to incarceration, 40 percent of those who were homeless reported use of mental health services or medications for a mental illness, a proportion twice that of non-homeless incarcerated individuals.

People with mental illness who were homeless prior to incarceration are two times more likely to have been exposed to trauma, specifically sexual and physical abuse, compared to those who were not homeless prior to incarceration. People with mental illness are also far more likely to be exposed to trauma while incarcerated, particularly sexual abuse, creating a vicious cycle of cascading physical and mental health issues that neither correctional institutions nor homeless service providers are adequately equipped to handle.

According to the Ending Community Homelessness Coalition (ECHO), 44 percent of Travis County’s homeless population reported experiencing mental health issues in 2017. As of June 26, 2018, 689 Travis County Central Booking inmates were coded as having a psychiatric condition; nearly 36 percent were homeless at the time of arrest.

Substance Use

A study analyzing individuals in the San Francisco County Jail system found that 78 percent of incarcerated people who were homeless at the time of arrest were significantly more likely to receive a psychiatric diagnosis and a diagnosis of a cooccurring substance-related disorder; and 78 percent of those with a severe mental illness also had a co-occurring substance use disorder compared to 69 percent of those with a severe mental illness who were not homeless. There is also a strong association between one’s history of imprisonment and substance use.

According to ECHO’s 2017 Needs and Gaps Report, 60 percent of Travis County’s homeless population reported having had an issue with drugs and alcohol at some point in their lifetime, and 17 percent reported consuming drugs and/or alcohol every day, or almost every day, for the past month.

Employment and Income

Adults in poverty make up approximately 11 percent of the population, yet they are three times more likely to be arrested than adults above the poverty line. Furthermore, individuals with incomes less than 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines are about four times more likely to be charged with a felony than the average person, and 15 times more likely to be charged with a felony than those with incomes higher than 150 percent of the federal poverty guidelines. At least a third of the U.S. inmate population falls under the poverty threshold at the time of arrest, making them more likely to be charged with a felony and more susceptible to homelessness upon their release, especially given the challenges of finding stable housing with a felony record.

According to ECHO’s 2017 Needs and Gaps Report, 67 percent of Travis County’s homeless population reported they cannot access employment or do not have earned income, and 36 percent reported having unresolved legal issues, which could result in incarceration or legal fines.

Criminalization of Homelessness

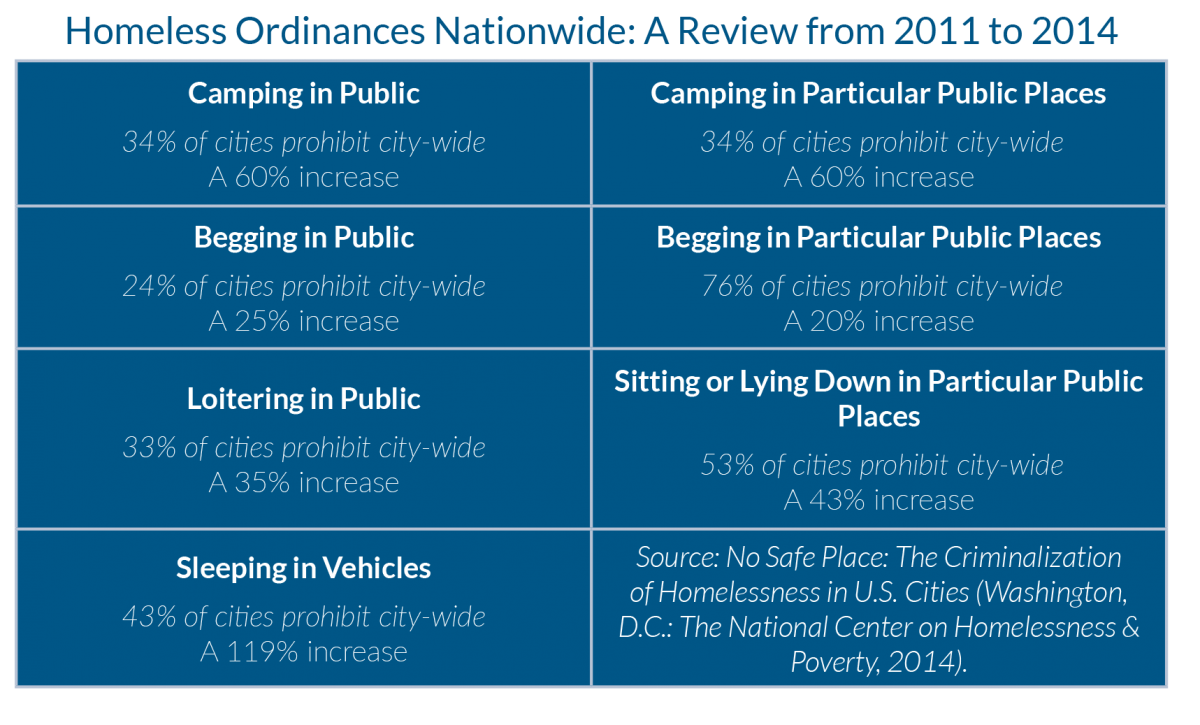

For the homeless population, the majority of justice system interactions are for nonviolent offenses that should not lead to incarceration. Homeless men and women are frequently arrested for minor crimes that are a direct result of their housing status, including Class C misdemeanor offenses such as panhandling, camping, sitting and/or lying in public spaces, loitering, sleeping in a vehicle, burglary of a vehicle, breaking and entering, trespassing, and shoplifting. These acts are often attempts to acquire shelter, food, or medical assistance as a means of survival.

One study in Austin found that homeless men comprised 4 percent of all arrests for violent offenses and less than 10 percent of arrests for all violent and property crimes. Yet, these very men accounted for roughly 40 percent of all arrests involving minor offenses such as drug-related offenses, city ordinances, trespassing, and disorderly conduct. This data exposed an arrest rate for homeless men nearly five times that of the rate for men in the general population. However, the majority of all arrests, minor or not, were for offenses in which there was no reported victim.

Challenges and Considerations

Lack of education creates an additional barrier to reentry. Nearly 70 percent of the U.S. incarcerated population is functioning at the lowest literacy rates, and only 32 percent of those in state prisons received a high school diploma. Currently, it is estimated that roughly 80 percent of Travis County’s Del Valle Correctional Complex population lacks a high school diploma.

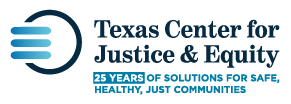

Barriers to housing and shelter are immense. The United States has lost roughly 13 percent of its low-income housing since 2001, a shortage felt most by those on the cusp of homelessness who must compete for the remaining affordable units. In Austin and greater Travis County, the fastest growing metropolitan area in the country with an average of 151 new residents each day, the barriers are amplified. As more and more residents flood the housing market, viable options for formerly incarcerated homeless individuals are challenging to locate.